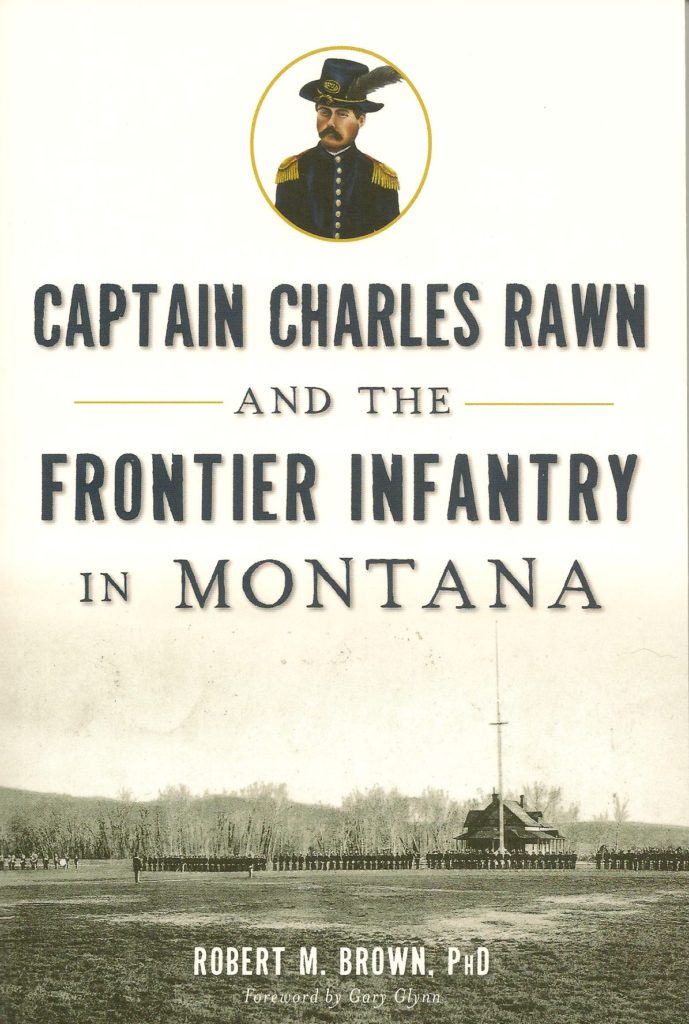

My friend Robert M. Brown has published a new book on Captain Charles Rawn and the Frontier Infantry in Montana, published by History Press in 2016.

Bob asked me to write a foreword for the book, which I was happy to do and which can be found below. Check it out. It’s a good book!

Foreword to Captain Charles Rawn and the Frontier Infantry In Montana by Robert M. Brown

I first encountered Captain Charles Rawn on a fine spring day at the site of Fort Fizzle, scene of a confrontation in Montana’s Lolo Canyon between hundreds of Nez Perce warriors and a small contingent of U.S. Army soldiers and local civilians. Dressed in an impeccable blue uniform trimmed with gold braid, wearing a black campaign hat and armed with a single-action pistol, Captain Rawn cut an imposing figure as he described the events of the 1877 Nez Perce War to a group of local schoolchildren. They listened raptly as Rawn described his role as leader of the small force at Fort Fizzle and told of his unsuccessful attempts to negotiate a peaceful surrender with the Nez Perce leaders, including Looking Glass, White Bird, and Joseph. Most of the schoolchildren who learned the story of Fort Fizzle from Major Rawn never realized that the uniformed figure who portrayed Rawn was in fact Dr. Robert M. Brown, the Executive Director of the Historical Museum at Fort Missoula. Rawn was the founder and first commander of Fort Missoula, and Dr. Brown spent years researching his historic alter-ego, making him uniquely qualified to write the story of one of the little known but important figures of the frontier army. Whole bookshelves have been filled with biographies of a few prominent soldiers who fought the Indian wars, in particular Lt. Col. George A. Custer, who famously lost his entire battalion after a rash attack on a vastly superior force. On the other hand there has been little written of the everyday lives of the mid-level officers of the frontier army, those men who were focused on doing their jobs and keeping their men alive, rather than seeking fame and promotion. Rawn was raised in an upper middle class family in Pennsylvania, yet chose a career that would take him away from the comforts of civilization for years at a time. He and his family would spend most of their lives in a near lawless land where a small number of soldiers were tasked with keeping an uneasy peace between newly arrived settlers and the Native Americans who had occupied the land for millennia. It is telling that when the U.S. Army drastically downsized at the end of the Civil War, many well-regarded officers were mustered out of service. Rawn on the other hand was not only retained as an officer, but kept his war-time rank of captain while many of his peers faced major reductions in rank. Rawn’s story provides insight into the hardships experienced by those who chose a career in the post-war military, which for most officers proved a thankless job with little chance for advancement and was often characterized by a frustrating series of postings to remote forts. Who were these men who chose to serve their country for little pay or recognition? What motivated them to remain as career military officers despite harsh living conditions? In Captain Charles Rawn and the Frontier Infantry in Montana, Dr. Brown has given us a rare and long overdue insight into the day-to-day lives of the front-line officers who were the backbone of the frontier army during the last half of the Nineteenth Century. Gary Glynn, author of That Beautiful Little Post: The Story of Fort Missoula