MEAGHER OF THE SWORD

The colorful leader of the Irish Brigade fought many battles

—not all of them with the enemy.

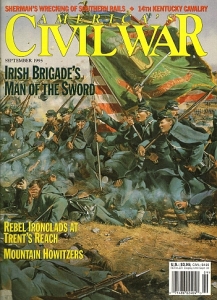

Originally published in America’s Civil War September 1995

By Gary Glynn

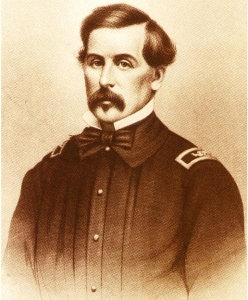

The bronze statue of Brigadier General Thomas F. Meagher depicts a dashing man astride a prancing horse, waving his sword over his head and urging the Irish Brigade into battle. One of the Civil War’s most colorful generals, Meagher (pronounced Mar) successfully led the legendary Irish Brigade of the Army of the Potomac through some of the fiercest battles of the Civil War, including the Seven Days’ campaign, Antietam, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. Meagher then used his military experience as a springboard to high political office, a career cut short by his mysterious death.

Born into a wealthy family in Waterford, Ireland, on August 8, 1823, Thomas F. Meagher showed his true character at an early age. Undeniably talented, Meagher was often described as ‟truculent, noisy, brash, verbose, and belligerent.” Barely out of his teens, the well-educated Meagher became a leading spokesman on behalf of the Irish independence movement. A skilled orator, he also demonstrated a lifelong propensity for making enemies and creating public furor. The world first heard of young Thomas Meagher in 1846, after he spoke before a hostile audience in Dublin, where he urged the violent overthrow of British rule on the Emerald Isle. He cited the examples of the American Revolution and armed revolts in Belgium and Austria, repeating the mocking refrain, ‟Abhor the sword? Stigmatize the sword?”

Interrupted in mid-speech by moderates in the crowd who disagreed with his position, Meagher and his supporters in the Young Ireland movement stormed out of the hall. The Dublin speech that made him famous was widely published, and “Meagher of the Sword” continued to tour Ireland, speaking to rowdy and sometimes violent audiences. It was not long before the young revolutionary attracted the notice of British authorities.

On March 21, 1848, Meagher was arrested and charged with seditious libel. The charge was eventually dismissed, but British authorities were becoming increasingly concerned about Meagher’s revolutionary activities. He was again arrested during the late summer of 1848, and this time he was found guilty of sedition and treasonous activity. He was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered, but his sentence was later commuted to banishment tor life, and Meagher was shipped to the penal colony of Tasmania, where he lived uneventfully tor several years.

The Bettmann Archive

Meagher was not content to live out his life in exile, however, and with the help of two sailors he secretly rowed to a tiny island between Australia and Tasmania, where, by prearrangement, he was picked up by boat 10 days later. He arrived in New York City at the end of May 1852 and found himself an instant celebrity. The large Irish community in New York welcomed his arrival with wild enthusiasm. Thousands of people cheered him in the streets, and parties were thrown in his honor.

Described as “a fine, military-looking young gentleman, stoutly built, handsome, and always a favorite with the ladies,” Meagher soon married a girl from a wealthy New York family. He became a U.S. citizen and was admitted to the New York bar in 1855. Like so many of his other professions, his law career was undistinguished, although Meagher did serve as an associate lawyer during the celebrated murder defense of Daniel E. Sickles, a man destined to become a major general in the Union Army of the Potomac.

The Sickles trial was one of the most sensational in American history. In 1859, Sickles, a well-known New York congressman, shot and killed Washington, D.C. socialite Philip Barton Key, the son of composer Francis Scott Key, on the streets of the capital. Key, according to rampant rumors, had been having an affair with Sickles’ beautiful young wife, Theresa. When Sickles inevitably heard the rumors, he forced his wife to confess and sign an admission of her guilt. Then, catching sight of Key on the street in front of the Sickles’ home, the outraged husband pulled a pistol, shouted, ‟Key, you scoundrel, you have dishonored my house—you must die!” and fired two bullets into the unarmed seducer. A stellar group of defense attorneys, headed by future Union Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, managed to convince a jury that Sickles was innocent by reason of “temporary insanity,” the first time such a plea had been used successfully.

Meagher’s law career could not support him, however, and he founded a newspaper, the Irish News, in 1856. He also continued his speaking tours. Of his varied careers (orator, editor, lawyer, soldier, politician), he was most successful at lecturing. He traveled throughout the United States and Central America, and he was particularly impressed by the Southern states.

Meagher, a confirmed Democrat, declared his sympathies for the South during the spring of 1861, but he soon realized his was an unpopular position in New York. The Civil War was only a few weeks old when Meagher pledged, “My heart, my arm, my life—to the national cause.” And once he-had decided to back the Union cause, Meagher moved swiftly. Although he had no military experience, he advertised in the newspapers for 100 Irishmen to form a company of Irish Zouaves under his leadership. By June 1861, the now Captain Meagher and his Zouaves were attached to the 69th New York Militia, an all-Irish unit commanded by Colonel Michael Corcoran.

Clear the Way painting by Don Troiani

At the First Battle of Bull Run, the 69th arrived at the Stone Bridge on the Warrenton Turnpike before dawn on July 21, 1861. The 69th, which divisional commander Colonel William T. Sherman considered his most reliable regiment, came into the battle on the Sudley Springs Road, crossed the Warrenton Turnpike, and struck the Confederate line near the Henry house.

Meagher swung his sword over his head. “Come on, boys, here’s your chance at last,” he urged. Three times the 69th attacked uphill toward the Confederates, and three times they were repulsed in very heavy fighting. The color-bearers, carrying the green flag of the 69th into combat for the first time, became targets for Rebel sharpshooters. Despite a valiant effort by the Irishmen, the enemy artillery forced them back. One relieved Confederate officer noted that, “the Irish fought like heroes.”

During the battle, Meagher was knocked head over heels and fell senseless on the field. He was saved from certain capture by a former neighbor from New York who recognized him. “A private of the United States Cavalry, galloping by, grasped me by the back of the neck, jerked me across his saddle, and carried me a few hundred yards beyond the range of the batteries,” Meagher later recalled.

The 69th retreated in good order, but left almost 200 of their number on the field, dead, wounded or missing. Most of the Federal troops, however, were fleeing the field in disorder, and the 69th joined the rout. Jubilant Confederate cavalry swept into the disorganized Federals, and Colonel Corcoran and many of his men were captured.

The dazed Meagher was put aboard an artillery caisson as it rumbled back to Washington. At Cub Run Bridge, Confederate cavalry overtook the column of fleeing Federals and opened fire. One of the horses pulling the caisson was shot and the wagon overturned, dumping the already shaken Meagher into the water. The overturned wagon blocked the road, causing additional panic among the fleeing troops, many of whom did not stop running until they reached the outskirts of Washington, D.C., 35 miles away.

After the disaster at First Bull Run, the 69th New York State Militia saw no further service. In August 1861, the 90-day soldiers of the 69th were mustered out of the service. Many of the veterans immediately signed up for service with a new unit, the 69th New York State Volunteers. With Colonel Corcoran now a prisoner, Captain Meagher, one of the most prominent Irishmen in New York, was promoted to major of the 69th.

It was not long before the persuasive and ambitious Meagher talked the government into allowing him to form an Irish Brigade. Meagher spoke before 30,000 potential recruits at one event in New York City, and he also traveled to Boston to address the Irish community there. Many of the new recruits were not motivated simply by patriotism. Encouraged by Meagher, they considered service in the Union Army a good way to obtain military training for an eventual armed invasion of Ireland.

Meagher, who was promoted to acting brigadier general, spent much of the fall of 1861 raising the regiments of the Irish Brigade. Besides the 69th, the brigade originally consisted of two other regiments of New York State Volunteers, the 63rd and the 88th. Mrs. Meagher was adopted as honorary colonel of the 88th, which was formed around the core of Meagher’s Zouave company. At various times the 28th Massachusetts, 29th Massachusetts (non-Irish), 116th Pennsylvania and several artillery batteries also served with the Irish Brigade.

The ‟Sons of Erin” carried distinctive green flags, embroidered in gold with a harp, shamrock and sunburst. Officers wore green plumes in their hats, while the colorful Meagher was partial to green jackets, embroidered with far more gold lace than regulations called for, set off by a yellow silk scarf. According to one Pennsylvania soldier, he was, “a picture of unusual grace and majesty.” Of the 2,500 men who initially enrolled in the brigade, at least 500 were veterans of Bull Run, and many more had fought with foreign armies. Late in November 1861, the 63rd Regiment left New York amid a riot on the docks. Thousands of civilians bid their boys farewell. The crush of the mob was so great that Meagher’s horse was nearly pushed into the path of a train as he was trying to get his soldiers aboard.

Upon arrival in Virginia, the brigade was assigned to the 1st Division of Brig. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner’s II Corps. Meagher’s men spent most of the spring in training at Alexandria. Meagher soon earned a reputation as a good host, plying his guests with liquor and sparkling conversation. The Irish Brigade’s parties quickly became as legendary as their fighting spirit. On May 31, 1862, the brigade sponsored a horse race, the Chickahominy Steeplechase. In the middle of the race, Confederate forces under General Joseph E. Johnston attacked Federal forces at Fair Oaks (Seven Pines). General George McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, immediately sent Sumner’s II Corps to reinforce the Union line. For the men of the Irish Brigade, that afternoon and night seemed an endless march. They crossed the Chickahominy River and, exhausted, fell asleep for a few hours amid the grisly wreckage of the previous day’s battle.

On June 1, the 69th and 88th New York Volunteers went into action with a half-English, half-Gaelic battle cry that compared favorably with the dreaded Rebel yell. They stopped the advance of two brigades of Confederates, then acted as a rear guard while other Federals escaped to the north side of the Chickahominy. Although the Irish Brigade was not in the worst of the fighting, it still lost 39 killed, wounded, captured or missing at Fair Oaks.

It was in the Seven Days’ campaign, during that terrible last week of June 1862, that Meagher and his Irishmen first established their reputation. On June 27, after General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had broken through the Federal lines at Gaines’ Mill, Meagher’s men turned back stragglers fleeing the battle, effectively stopping the rout. They then fought a stubborn rear-guard action that bought McClellan a precious day to pull together his retreating Army of the Potomac. Confederate Brig. Gen. George Pickett credited Meagher’s men with fighting heroically and holding back the pursuing Rebels under general Thomas R. Cobb.

Two days later, the Irish Brigade and the rest of Sumner’s II Corps threatened the Confederate line in the morning, then were forced to withdraw to Savage’s Station. On that day, June 29, Meagher was temporarily placed under arrest, but the charges could not have been too serious. By the next day, he was conspicuous riding up and down the front line at White Oak Swamp, directly in front of the forces of Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. As Jackson shelled the Federal line, Meagher declared, “I would rather be killed riding this horse than lying down.”

As June of 1862 turned into July, Lee attempted to destroy the battered Union army at Malvern Hill. Meagher was in the forefront of the savage hand-to-hand battle, exhorting his men to throw off their gear and charge with bayonets. By the time darkness brought an end to the Seven Days’ campaign, the famous green flags of the Irish Brigade were riddled by fire. In the space of just one week, the brigade had lost 700 men dead, wounded or missing. The brigade needed new recruits to bring it back up to strength, and McClellan gave Meagher permission to return to New York on a recruiting drive. Doing what he did best, Meagher spoke in front of 4,000 people in New York City on July 25, but the days of easy recruiting were gone.

When Meagher rejoined his unit, he brought with him only 250 new recruits, a mere quarter of those needed to fill out the ranks. By September 1862, the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia were headed toward their historic clash at Antietam. On the bloodiest day in American history, Meagher, his aides and the regimental chaplains led the way as the Irish Brigade crossed Antietam Creek, then moved uphill. They calmly tore down a fence in the face of tremendous artillery fire. The Rebels retreated to a sunken road, where they poured fire into the Irish Brigade and the rest of II Corps. Meagher yelled, “Boys! Raise the colors and follow me!”

Mort Kunstler Inc.

Five times, the men of the Irish Brigade charged the Confederate line at the so-called Bloody Lane, and five times they were repulsed. The color-bearers were easy targets, and eight men carrying the green flags were shot down at Antietam. In the face of withering fire, Meagher’s men halted on a little knoll 100 yards from the sunken road, with the Confederates directly in their line of fire. Running out of ammunition, the soldiers frantically searched the pockets of the dead and wounded for cartridges. One of Meagher’s aides was killed, and another had two horses shot from under him. In the thick of the battle, Meagher’s horse was also killed, and he was hurled to the ground unconscious. (At least one Federal officer claimed that Meagher was drunk and simply fell from his horse.) Although the general was not seriously hurt, early newspaper accounts of the battle reported that Meagher had been killed. Whatever the extent of his injuries, he had sufficiently recovered in time to arrange a truce with a Confederate officer the following day to retrieve the wounded. The regiments were torn to pieces on the little knoll, and they finally went to the rear, the 500 men still on their feet marching proudly in formation. Divisional commander Maj. Gen. Israel Richardson saluted one regiment as it passed. “Bravo 88th, I shall never forget you!” he cried.

After Antietam, President Abraham Lincoln again removed the highly popular McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac. Legend has it that as McClellan passed in review of his troops, the impetuous Meagher ordered the famous green flags thrown down in front of the general in protest of McClellan’s dismissal. McClellan halted and somberly ordered the flags picked up before he would pass.

The 1,300 survivors of the Irish Brigade underwent their next trial by fire that December at Fredericksburg. En route, Meagher ordered his men to cross the Rappahannock and capture an isolated Confederate battery. The men of the Irish Brigade stormed across a ford in the river, routed the defenders and captured two guns within minutes. An admiring Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock remarked, “General Meagher, I have never seen anything so splendid.”

With Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside now in command, the Army of the Potomac endured weeks of cold and rain while the Confederates fortified their positions at Fredericksburg. Although an assault on the Confederate defenses seemed suicidal, Burnside persisted.

Three pontoon bridges were thrown across the river, and on December 12, 1862, the Irish Brigade and the rest of II Corps crossed the Rappahannock. Each man of the brigade wore an evergreen sprig in his cap as the brigade moved through the ruined town, clearing it of snipers.

From the Confederate position on Marye’s Heights, Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill muttered, “There are those damned green flags again.” The green flags, in fact, were tattered beyond repair, all except for a new one carried by the 28th Massachusetts. (This flag was later found on the battlefield by a Confederate soldier of Irish ancestry. Shortly after the battle, the Confederate impulsively swam across the river to return the flag to Meagher.) New green flags for the Irish Brigade had in fact been brought to Fredericksburg by several distinguished citizens from New York City. Wagonloads of food and drink had also been ordered for presentation with the flags, but the ensuing battle intervened.

On the morning of December 13, Meagher ordered the 69th New York to lead the brigade down Hanover Street toward the canal. The men anxiously watched as Maj. Gen. Samuel French’s division was cut down, and then it was their turn to face the fire. Under intense fire, they began pushing toward the very center of the Confederate defenses on Marye’s Heights.

The Irish Brigade’s actions at Fredericksburg won its men the admiration of all who were present. Pushing uphill toward the center of the entrenched Confederate line, the brigade never wavered despite the murderous fire. The Confederates watching from the heights were particularly impressed. Lieutenant General James Longstreet thought the charge of the Irishmen “was the handsomest thing in the whole war.” Robert E. Lee admiringly declared, “Never were men so brave.” Pickett, who would make his own legendary charge within the year, thought “the brilliant assault…. was beyond description…. we forgot they were fighting us, and cheer after cheer at their fearlessness went up all along our line.” Thomas F. Galwey, a Union soldier in French’s division, had a bird’s-eye view of the Irish Brigade’s charge: “They pass just to our left, poor fellows, poor, glorious fellows, shaking goodbye to us with their hats!” Galwey saw the brigade “reach a point within a stone’s throw of the stone wall. No farther. They try to go beyond, but are slaughtered. Nothing could advance further and live. They lie down doggedly, determined to hold the ground they have already taken. There, away out in the fields to the front and left of us, we see them for an hour or so, lying in line close to that terrible stone wall.” It was no use. The Confederate line was too strong, and little by little the Irishmen began crawling back down the hill.

The Irish Brigade had been shattered. By evening, only 250 men of the 1,300 who had charged up the hill were present and accounted for. Almost 500 men had been killed or wounded; one company was down to three men.

Despite the carnage, that night the new green flags were presented to the Irish Brigade. The survivors commandeered a shell-damaged building in Fredericksburg. Liquor flowed freely, large tables of food were set out, and Meagher topped the list of speakers. The party was so loud that Burnside’s headquarters heard the commotion on the far side of the river and ordered the festivities stopped before the Confederates resumed shelling.

Meagher’s reputation as a good host was further enhanced during March 1863, when he invited the new army commander, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, as well as his staff and most of the II Corps officers, to a gala St. Patrick’s Day banquet. Featured entertainment included a steeplechase, watched by 20,000 Federal soldiers, as well as footraces, wheelbarrow races, horse races, and a greased pig chase. One officer remembered that Meagher served “the strongest punch I ever tasted.” Meagher himself overindulged and challenged his brigade surgeon to a duel, but their differences were apparently patched up by the next day.

Spring brought campaigning weather, and once again the Army of the Potomac, including the 520 surviving members of the Irish Brigade, crossed the Rappahannock and moved on Chancellorsville. On May 3, 1863, as Lee’s troops rolled up the Federal line, the Irish Brigade supported the 5th Maine Battery in trying to stem the Confederate advance. Thirty Rebel cannons pounded the six guns of the 5th Maine, destroying most of the caissons and killing the horses. Stubbornly retreating, the Irishmen saved the guns, dragging them backward by hand as their numbers were thinned even more.

A few days after the debacle at Chancellorsville, the impetuous Meagher made the worst mistake of his military career. Protesting the wasting away of what he called “this poor vestige of and relic of the Irish Brigade,” Meagher resigned his command on May 6, 1863. He intended to return to New York and devote all of his time to raising a fresh brigade, even though his previous recruiting trips had been unsuccessful. He turned over command to Colonel Patrick Kelly and left the brigade on May 19.

Meagher returned to New York City, but his dream of raising a new unit was shattered by the July draft riots in the city, riots in which the Irish community played a conspicuous, disreputable part. With little else to do, Meagher lobbied for a new military command or the governorship of one of the new western territories.

Eighteen long months passed before the Army found a place for Meagher. Finally, in the tall of 1864, he was sent south to the Department of the Cumberland, where he was handed the thankless task of making a fighting unit out of some 5,000 stragglers, convalescents and garrison troops. The general’s heart was not in his new command, however, and he did little to whip his men into shape. Meagher’s Provisional Division, described as “a mob of men in uniform,” was shipped to New Bern, N.C., in January 1865. One witness described the men of the division as “ill treated and suffering, badly managed, shamefully deserted by drunken officers.”

It was at this point in his career that Meagher’s excessive drinking became so noticeable that the military could ignore it no longer. On February 5, 1865, Major Robert N. Scott delivered orders to Meagher and found the general so drunk that he could not understand them. Three weeks later Meagher was relieved of further duty, amid rumors of court-martial proceedings. As the Confederacy was driven to its knees, Meagher returned to New York. He resigned his commission on May 15, 1865.

In appreciation of his service in command of the Irish Brigade, the state of New York awarded Meagher a gold medal. His gaudy uniform abandoned in favor of civilian clothes, the disgraced Meagher walked in the Fourth of July parade in New York City along with the surviving members of the Irish Brigade.

With his military career ended in near disgrace, the silver-tongued Meagher began looking for civilian work, preferably a long way from New York. During his sojourn in New York City in 1863 and 1864, Meagher had managed to offend much of the local Irish community. He had implied that many Irish were involved in the deadly New York draft riots, and had accused the “obstinate herds” of Irish Democrats of “gross stupidity” and “the stoniest blindness.” His military accomplishments were not enough to erase those harsh remarks.

Shortly after leaving the military, Meagher embarked on the last great adventure of his life. In response to a veritable flood of letters from the Irishman, President Andrew Johnson appointed Meagher to be the new secretary of Montana Territory.

Meagher, as usual, managed to involve himself in controversy almost from the beginning. He arrived in the raw gold-mining camps of Montana in September 1865 and immediately found himself the acting governor of Montana. For almost two years, the flamboyant Meagher cut a wide swath through Montana politics, alternately infuriating Democrats and Republicans alike.

True to form, Governor Meagher did his best to incite a war with the Sioux tribe. Seeking arms for the militia he had raised, Meagher traveled to Fort Benton to meet a Missouri River steamboat that was bringing cases of rifles. A friend, finding the general ill after several days’ travel, offered him a berth on board a docked steamboat.

Late that night, a watchman aboard the steamboat saw an indistinct white figure plummet from the upper decks of the boat. When he heard a splash in the water, he roused the crew. Searchers with lanterns checked both banks of the Missouri around Fort Benton, but no trace of the missing governor was ever found.

The incident that ended the life of the colorful, combative Irishman has been shrouded in mystery ever since. Some people theorized that Meagher had been drinking and had accidentally fallen off the boat. Others thought he had committed suicide, or that he had been murdered by his political enemies in Montana Territory. No matter, Thomas Francis Meagher had made his last exit from the world stage.

Despite a life of some accomplishment militarily and otherwise, Meagher never achieved the grand success he sought. One solid reminder of his achievements remains, however. On the front lawn of the Montana Capitol in Helena a bronzed statue of the fiery general sits on horseback, saber raised, ever ready to charge into battle.

Gary Glynn is the author of Montana’s Home Front During World War II. His Article ‟Black Thursday For Rebels” was published in the .January 1992 issue of America’s Civil War. For further reading, he suggests: Thomas Francis Meagher: An Irish Revolutionary in America, by Robert G. Athearns; and The Irish Brigade, by .John Paul Jones.

Read Gary Glynn’s article on the Battle of Sayler’s Creek