A full account of the Bicycle Corps can be found in That Beautiful Little Post: the Story of Fort Missoula.

In 1896 a far‑sighted Army officer named Lieutenant James A. Moss of the 25th Infantry learned that several European Army’s were experimenting with bicycles, and he began his own tests on the suitability of bicycles for military purposes at Fort Missoula, a frontier military post in Montana. Although the officers were white, the 25th Infantry was a “crack black regiment.”

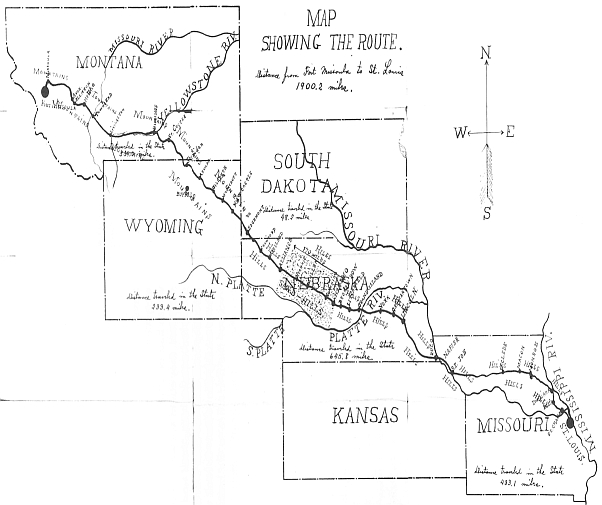

Moss sent his uniformed cyclists pedaling through the valleys of western Montana in the summer of 1896, delivering messages to remote outposts. By the end of the summer, Moss and his men embarked on an eight hundred mile tour of Yellowstone National Park which proved so successful that Lieutenant Moss decided to push his bicycle corps to the limit, and during the winter of 1896 he planned a new trip. His goal was St. Louis Missouri, half a continent away. Since many of the roads in the West were little more than unimproved horse trails, Moss planned to follow the route of the new Northern Pacific railroad to Billings, then along the route of the Burlington railroad to St. Louis. Knowing he had no sag wagon to rely on, Moss chose his route carefully, shipping supplies and spare bicycle parts to fourteen railroad stations along the route.

“Bad roads, Hard Winds, Alkali Water, Rattlesnakes and many other pleasures” was how a local newspaper described the United States Army’s first extensive test of the bicycle. Armed with the grandiose title of the Fort Missoula Bicycle Corps, twenty‑three soldiers pedaled their heavy, balloon‑tired bicycles past the front gate of a frontier military outpost in Montana on a cloudy gray day in 1897. The cyclists (they preferred to be called wheelmen) were headed to St. Louis Missouri, nineteen hundred unpaved miles from their starting point. Members of the 25th Infantry, they carried rifles, ammunition, and camping gear as they pushed their bikes through a blizzard on the Continental Divide, dealt with hailstorms, rattlesnakes, intense heat, and roads that were never intended for bicycling. Mud clogged their tires, rain soaked them day and night, and illness, “skeeters”, and exhaustion took their toll; nevertheless, their forty day journey to St. Louis was an unqualified success.

Newspapers across the country, including the New York Times, had been following the progress of the Bicycle Corps, and in Lincoln Nebraska the cyclists were mobbed by so many curious citizens that they were forced to camp on the statehouse lawn. On the following day they met a family of German immigrants who plied the hungry soldiers with milk, bread, cookies, and cake. Edward Boos reported “when the corps left the place I dare say that not a crust remained in the bread box of the dear woman.”

On July 24, forty days after leaving Fort Missoula, the Bicycle Corps were escorted into St. Louis by local bicycle clubs. Thousands of curious onlookers lined the streets as they pedaled the last few miles to their campsite at Forest Park. The weary troopers regaled local cyclists with their adventures, while Moss, Kennedy and Boos were entertained by the leading citizens of St. Louis.

A few days later, the soldiers cheered the news that they would be returning to Montana by train. Despite the rain which had plagued them two out of every three days, Lt. Moss and his men had conclusively demonstrated that bicycling was an effective means of military transportation. Although one man had been unable to keep up and had returned to Missoula halfway through the trip, the soldiers and their bicycles had stood the trip remarkably well. Resting only two days out of forty, they had averaged forty‑seven miles a day on their nineteen hundred mile journey.

Read more about the history of Fort Missoula and the Fort Missoula Bicycle Corps