Bert Fraser, commander of the Immigration and Naturalization Service’s Fort Missoula Detention Center, announced that the camp would be formally closed during the spring of 1944. Hundreds of Italian detainees and 293 Japanese had been paroled on work release, and most of the 310 Italians still interned in the camp left town by train on April 3, 1944, although some remained behind to help close the facility. One hundred recently arrived German civilians were sent to work for the Forest Service, while most of the remaining Japanese detainees were sent to camps in the South.

Community leaders worried that the loss of jobs from the detention camp would hurt the local economy, but Rep. Mike Mansfield managed to pull some strings and soon notified the local Chamber of Commerce that Fort Missoula would be turned back over to the Army to be used as a detention camp for medium-security military prisoners.

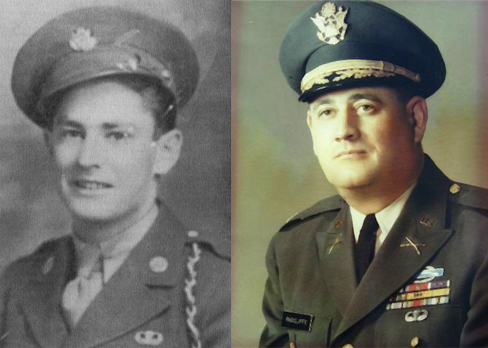

The Immigration and Naturalization Service formally transferred Fort Missoula to the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army in July 1944, and the Fort Missoula camp was renamed the U.S. Disciplinary Barracks, Northwestern Branch. Two thousand medium-security disciplinary prisoners were transported by rail from Leavenworth, Kansas to Missoula during the late summer of 1944. Col. Alexander M. Weyand commanded 535 Military Policemen and 130 civilian employees at the camp. (There were only 62 civilian and Border Patrol guards at the Alien Detention Center.)

The larger number of guards were needed. The army prisoners presented authorities in Missoula with far more problems than the Italian and Japanese detainees who had been housed there for the past several years, and who had made few escape attempts. Umberto Benedetti explained that, “no one really wanted to escape because they were treated very well by the people of Missoula.”

The American prisoners quickly demonstrated that the Fort Missoula facility was not totally secure. During the first week of October eight prisoners being held for desertion and for being absent without leave (AWOL) escaped from the camp, including one who was described as particularly dangerous. One of these escapees burglarized the nearby house of rancher David Maclay and got away with a considerable amount of cash. He was apprehended in Iowa six weeks later and given a six-year sentence for the escape and theft. Four more prisoners escaped in a hail of gunfire on October 16, 1944, although one was later recaptured at Dixon. Three days later a prisoner was killed, another wounded, and a third recaptured during an escape attempt. Ten prisoners escaped from Fort Missoula on November 27, although three were recaptured near Noxon, and six were caught near Polson after a 90-mile-an-hour car chase in which police fired repeatedly at the fleeing car. The last escapee was captured in Missoula a few days later. At the request of irate citizens, a siren was installed at Fort Missoula to warn residents when an escape attempt was underway.

The siren blew frequently, but didn’t stop the escapes. Three more men got away during the first week of December after scaling the fence while guards fired at them. Two of these men were captured near Lolo, and the other one, who had escaped once before, was apprehended near St. Ignatius. Eight of the recaptured prisoners were sentenced to an average of 17 years behind bars.